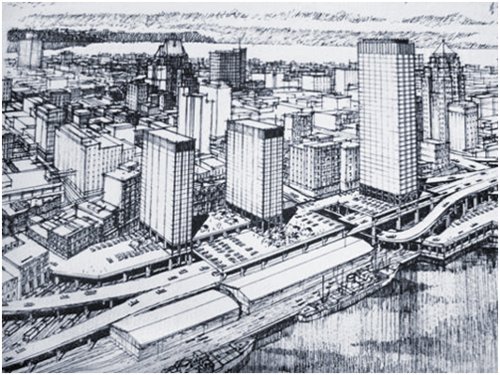

An artist’s depiction of the Downtown Vancouver that might have been.

http://www.raisethehammer.org/article/1427/a_distant_mirror:_40_years_of_urbanism_in_vancouver

The Freeway Proposals and Mass Opposition

Unlike other major North American cities, when an extensive network of freeways was proposed to support extensive development in Vancouver in 1967, angry citizens raised a storm of opposition and succeeded in blocking the vast majority of the proposed improvements [1]. In the face of near unanimous opposition lead by business owners of the Chinatown-Strathcona district, whose neighborhood was slated to be divided by a multilane highway, as well as the resignation of planning commission chair, almost all of the original freeway proposals were scrapped [1]. Though part of the opposition stemmed from the realization that freeway alignments were being dictated by landed interests such as the Canadian Pacific Railroad’s development arm, the National Harbours Board, and BC Hydro, another major source of opposition reflected the growing realization that the proposals simply represented bad planning. When an exasperated Vancouver mayor Tom Campbell notoriously commented that the freeway plan was being derailed by none other than “Maoists, Communists, pinkies, left wingers, and hamburgers” (his personal derogative term for people without a college education) it was clear that the city government and planning establishment was out of touch with the desires of the people [1]. By 1972 real change began to take shape as the pro-freeway/tunnel conservatives were decidedly defeated in the election [1]. Shortly thereafter, a growing consensus developed among the planning community, the Downtown Business Association, and residents began to throw their support to public transit.

Of the myriad of originally planned downtown freeways, tunnels, and bridges, few of them were ever built in their original configuration. The infamous Chinatown route was abandoned altogether, but two viaducts extending Georgia and Dunsmuir streets were built in 1971 and stand as a testament to the blight, division, and innumerable other downtown freeway related problems that might have been [1]. As John Punter puts it, “the citizen campaigns against the freeways in Vancouver were a pointed expression of the changing political climate in the late 1960s” [1]. A seminal reminder of this metropolitan change of heart was the eventual fate of a major freeway supported redevelopment project advanced by a consortium of business interests known as Project 200. Originally envisioned as a pedestrian deck and 14 high rise towers over the Canadian Pacific Railroad tracks at the Northern edge of Downtown, project 200 would eventually be scaled down in the 1970s to a single parking garage, a telecommunications center, an office building, and a pedestrian plaza served by a transit station [1]. This reversal of public opinion and eventually planning policy would soon be reinforced by the expansion of rapid transit in the next few decades.

An Expo Line SkyTrain in Vancouver

Expo ’86 and SkyTrain: The Beginnings of Change

In 1986 Vancouver’s economic fortunes began to improve in the wake of the 1986 Expo as city residents got their first taste of rapid transit with the introduction of the first SkyTrain transit line [1]. In addition to bringing about serious residential and commercial redevelopment in downtown and similar effects in a nodal configuration around suburban SkyTrain stations, Expo 86 also “raised public expectations for street life, design quality, and amenities” [1] contributing to the elevated public planning discourse in Vancouver today. According to the Translink website, “SkyTrain is the oldest and one of the longest automated driverless light rapid transit systems in the world” [2]. Since the eighties, an additional two SkyTrain lines have entered service in Vancouver: the Expo and Millennium SkyTrain lines connect downtown Vancouver to Burnaby, New Westminster, and Surrey while the Canada line connects downtown to the airport and the city of Richmond [2]. SkyTrain has and continues to influence Vancouver’s development and will most likely continue to do so for the foreseeable future as new lines (such as the Evergreen Line which is already under construction and is scheduled to open in 2018 at a cost of over $1.4 billion) and extensions of existing lines (such as the planned Broadway SkyTrain Extension) enter service [3]. For good or for bad, the autonomous, largely grade-separated SkyTrain rapid transit system has become an international symbol for the City of Vancouver and British Columbia.

A unique aspect of the Canada Line (the newest segment of Vanouver’s Skytrain system) is that it was financed in part by a public private partnership. Though intended to reduce upfront and operations costs, the public private partnership financing structure has been criticized due to lack of transparency, limited competition, and warped priorities. With regard to the public-private partnership behind the Canada Line, Matti Siemiatycki argues that with “only limited transparency and availability of information, the public was limited in their ability to criticize the official discourse in a cogent manner and to act as a strong counterbalance to the pressures that are inherent in the planning of all major transit projects” adding that the planning framework virtually limited the competition of ideas to those which supported a private–public partnership” [4]. The Canada Line took resources away from other important transportation services like needed expansions to the bus fleet, it resulted in the rerouting of a number of bus lines towards Skytrain stations rather than to downtown directly, and it resulted in the closure of the acclaimed B-Line rapid bus service which used to run on a parallel route [4]. While none of those changes are necessarily for the worst, when you take into account the fact that 74% of transit trips in Vancouver are taken by bus and that the Skytrain could only hope to offset about 6% of personal vehicle trips the cost benefit analysis starts to look increasingly warped [4]. Ultimately, the long term success of the Canada Line remains to be seen but the controversial nature of its financing scheme and the priorities behind them certainly dim the shine of an otherwise fast, autonomous, and largely grade separated transit link that efficiently shuttles people from Downtown Vancouver to the Vancouver International Airport and the large southern Vancouver suburb of Richmond.

Greenest City 2020 Plan: an Ambitious Vision

Envisioned in 2011 as a means to prepare the city for climate change, the Greenest City 2020 plan is set to reinforce the city's position as a global leader in green technology and sustainable development while simultaneously fostering the local economy through the creation of green jobs [5]. The Greenest City 2020 plan is the planning document that encompasses the City's extraordinary goal of becoming the greenest city in the world by 2020. In addition to general sustainability strategies, the Greenest City 2020 plan also called for the elevation of walking, cycling and public transit to the status of “preferred transportation options” over the automobile which dominates traditional transportation approaches [5]. The primary transportation-related targets of the aforementioned plan are to “make the majority (over 50%) of trips by foot, bicycle, and public transit” and to “reduce the average distance driven per resident by 20% from 2007 levels” [5]. In addition to mode share and auto-related targets, the Greenest City plan also calls for more subtle changes such as land use changes to support transit, unbundling of parking from the cost of housing, and increased transit service levels [5]. The Greenest City plan has already inspired a number of projects and planning efforts in response to the ambitions goals established when it was adopted by the City of Vancouver Council back in 2011.

Transportation 2040 Plan, Mode Share, and Moving Beyond the Car

Where transportation is concerned, the recently adopted (2012) regional transportation plan (Transportation 2040 Plan: A Transportation Vision for the City of Vancouver) is the long range planning document that presents a detailed vision for the future of transportation in the city and reflects the sustainability goals established a year earlier with the Greenest City plan. Like its predecessor, the 2040 plan is also centered on sustainability and emphasizes transit and active transportation mode share in the interests of fostering a livable city. For example, the plan estimates that 40% of all trips in Vancouver were taken on foot, bike or transit in 2008 but calls for that number to grow to half of all trips by 2020 and two thirds of all rips by 2040 [6]. Moreover, while population and jobs have increased since 1996 by 18% and 16% respectively the number of vehicles entering the city has declined by 5% reflecting the city’s commitment to active transportation and public transit [6]. To encourage even more people to forgo their cars in favor of walking, bicycling, or taking transit, Vancouver plans to expand its all ages and ability cycling network, build new rapid transit lines building on the success of the SkyTrain system, optimize parking policy, widen sidewalks, provide more public spaces, and roll out a public bike share system [6]. Though Vancouver is already a relatively bike, pedestrian, and public transit friendly place, there is no doubt that the wide range of planned infrastructure improvements in the 2040 transportation plan will further advance the City’s already sterling reputation if effectively implemented.

Bike Share

Part of Vancouver’s efforts to make cycling a viable option for transportation as well as recreation is the City’s planned public bike share system (PBS) which is set to debut this year. Modeled on successful systems in places like Paris and New York, the Vancouver PBS system will be privately owned and operated and will comprise of 1,500 bikes at 125 solar powered stations when it opens later this year [7]. When completed, the Vancouver PBS will help fulfill the sustainable vision of the 2040 transportation plan and keep Vancouver on track to meet its ambitions environmental and transportation goals for 2020, 2040, and beyond.

Beyond Vancouver: Regional Transportation Plans

The City of Vancouver does not operate in a vacuum, however, and its context within a broader region will necessitate continued cooperation between the city, its neighbors, and regional government. Luckily for Vancouver, the South Coast British Columbia Transportation Authority (formerly Translink), the regional governmental agency responsible for transportation, has very similar goals to metro proper. In 2008 the Transport 2040 plan was adopted codifying six goals for the metropolitan planning agency [8]:

1. A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from transportation

2. Most trips to be taken by transit, walking, or biking

3. Most jobs and housing to be located along the transit network

4. Travel is safe, secure, and accessible for everyone

5. Facilitation of economic growth and efficient goods movement through effective management of the transportation system

6. Stable, appropriate funding for Translink

In order to achieve these goals, Translink advocates the creation of Transit Orientated Communities (TOCs) that allow residents to drive less and walk, cycle, and take transit more [9]. This regional focus will result in the concentration of higher density, mixed-use, pedestrian orientated development nodes within walking distance from frequent transit stations in order to “support viable sustainable transportation choices” and create “communities that more livable, sustainable and resilient” [9]. These efforts to promote denser development outside of the city center at a regional scale will help ensure that Vancouver will be well served by transit, both within and beyond the city limits, for years to come.

In order to maximize the social benefits of TOCs, Vancouver employs a number of specialized legislative processes. For instance, the city typically requires 15% affordable housing for new development in TOC zones and that 5% of development cost must fund public infrastructure including “community centers and public space landscaping” [10]. Though these efforts are ongoing, maintaining a reasonable supply of affordable housing maintains a key challenge for the City as well as one that Transit Orientated Communities alone are unlikely to fix. One example of a highly successful TOC in Vancouver is that of Collingwood Village. Completed in 2006, Collingwood Village is a large (28 acre site), mixed use development including 2,700 residential units, 70,000 square feet of non-residential space including a grocery store, a drug store, and an Elementary School as well as a 10,000 square feet community center and a daycare [11]. Though the development is situated around the 8th stop from downtown Vancouver on the Expo SkyTrain line, distance to the transit station ranged from 80-2,300 feet and the development included almost 2,200 parking spaces drawing into question just how transit orientated it really is. Despite these modest concerns, the Joyce-Collingwood Station had an average ridership of 10,800 in 2005 and is considered “to be a highly successful example of transit-supportive densities and development, given the mix of uses, high residential densities, accessible pedestrian network, and reduced residential parking requirements” [11]. Moreover, the inclusion of over 2,400 bicycle parking spaces, changing rooms and showers at commercial buildings, small walkable blocks , and landscaped pedestrian routes and complete street treatments more than make up for the longer distances to the transit station from the periphery of the development as well as the expansive subterranean parking provision.

Part of the Collingwood Village Development from the SkyTrain Platform

https://pricetags.wordpress.com/2012/06/22/density-in-a-city-of-neighbourhoods-7a/

Key factors to the success of the Collingwood Village TOC include collaboration with the City and extensive coordination with the community resulting in strong community support [11]. Moreover, public support for building step backs and other design features were reflected in the design process and served to multiply resident support [11]. Parking requirements have been reduced over time as residents have demonstrated lower use patterns and 93% of residents surveyed indicated that proximity to transit had some influence or was the main reason that they chose to live in Collingwood Village with 32% in the latter camp [11]. The importance to transit to so many of the local residents surveyed and the high ridership figures of the local transit station speak to the success of Vancouver’s TOC program overall as well as the design of the Collingwood Village development.

References

1. Punter, J. (2003). The Vancouver achievement: Urban planning and design. Vancouver: UBC Press.

2. TransLink. (2015). SkyTrain. Retrieved February 10, 2015, from http://www.translink.ca/en/Schedules-and-Maps/SkyTrain.aspx

3. TransLink. (2015). Rapid Transit Projects. Retrieved February 10, 2015, from http://www.translink.ca/en/Plans-and-Projects/Rapid-Transit-Projects.aspx

4. Siemiatycki, M. (2005). The making of a mega project in the neoliberal city. City, 9(1), 67-83.

5. Canada, City of Vancouver. (2011). Greenest City 2020.

6. Canada, City of Vancouver. (2012). Transportation 2040 Plan: A transportation vision for the City of Vancouver. Vancouver, BC.

7. City of Vancouver. (2014, April 07). Public bike share system. Retrieved February 10, 2015, from http://vancouver.ca/streets-transportation/public-bike-share-system.aspx

8. Canada, Translink. (2012). Transport 2040. Vancouver, BC.

9. TransLink. (2015). Tranit-orientated communities. Retrieved February 10, 2015, from http://www.translink.ca/en/Plans-and-Projects/Transit-Oriented-Communities.aspx

10. Curtis, Carey, John L. Renne, and Luca Bertolini. Transit Oriented Development: Making It Happen. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate, 2009. Print.

11. "Transit-Orientated Development Case Study: , Collingwood Village, Vancouver, B.C." Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2009): n. pag. Web. 10 Mar. 2015.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete